What is the difference between marijuana, hemp and cannabis? This confusion over the difference is no accident, but rather part of a long campaign to marginalize cannabis.

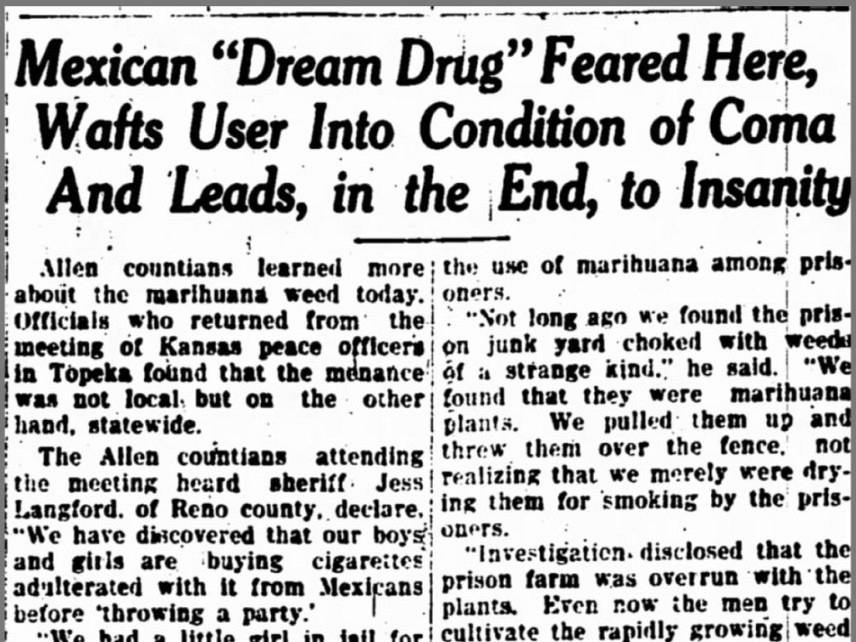

Donald J. Trump is definitely not the first businessman, politician or racist who uses verbal tactics to sow chaos and confusion. The field of drug policy has many who have used this ploy, including but not limited to William Randolph Hearst, a wealthy anti-Mexican newspaperman, and the extremely wealthy son of a silver baron, Harry Anslinger, a racist, ambitious federal bureaucrat. So when it comes to cannabis it’s easy to get confused by the vocabulary.

One of the first people to demonize cannabis was Pope Innocent VI in the 15th century as part of the Inquisition and the witch hunts. In a famous papal bull he demonized cannabis as a “tool of the devil”. While this was aimed at so-called witches, in point of fact they were actually herbalists and lay healers. Their “sin” was to know and use plants to treat medical conditions in lieu of faith. Their worst sin was knowing that cannabis could ease the pain of childbirth, which according to the clergy of the time, was punishment for Eve eating the apple from the tree of knowledge.

Notwithstanding the Pope’s opposition, until the late 19th century hemp was the most profitable agricultural plant in the world for 1,000 years. Cannabis appeared in every major materia medica since the Ping Ts’ao Ching in 2637 BCE, in an Ayervedic Medicine Pharmacopoeia dated between 1000-1700 BCE, Descordes in Rome 70 CE, the Ebers Papyrus 1500 CE, down to and including being in the United States Pharmacopoeia (USP) from the 1850s until 1942. At the dawn of 20th century cannabis was the third most common ingredient after alcohol and opium in prescriptions and patent medicine.

With the rise of the steamship, hemp was no longer much needed for sail and rigging, but it was still a valuable crop. In the 19th century Kentucky was the center of hemp growing in the U.S., but in the early 20th century Wisconsin and Minnesota were prime hemp growing states. Hemp was still used for rope and fiber and the oil was used in making paint. In the 1920s American physicians wrote three million cannabis containing prescriptions per year. So how did we get where we are today?

So, What Happened?

In the mid-19th century an influx of Irish-Catholic immigrants (a result of the potato famine in Ireland) came to the U.S. The English had long discriminated against the Irish and particularly Irish Catholics. This lasting animosity led the Temperance Movement to morph into a prohibition movement. This made the concept of prohibition more popular amongst anti-immigrant factions by the U.S. population.

Soon in the mid-19th century, millions of Chinese arrived on the West Coast. This was due to a devastating flood in China, destroying tens of thousands of acres of farmland. It was a matter of survival to come to the U.S. where there were plentiful jobs in and around the gold mines. A decade later the Chinese, along with the Irish and others, were pivotal in building the Transcontinental Railroad.

In 1873 the U.S. faced its first depression. Xenophobia was in full bloom. These Chinese not only worked too hard, they worked cheap, so they were accused of “taking our jobs”, but that wasn’t enough. The Chinese were accused of luring virginal, white, Protestant women into their opium dens. Soon opiates were added to alcohol as a substance that should either be prohibited or at the very least highly regulated.

Okay, hold on. I’m setting the stage and getting to cannabis. The origin of the word ‘marijuana’ is lost in antiquity. Cannabis is said to be found in the Bible as Kaneh Bosm. Some theorize that Jesus of Nazareth used tincture of cannabis as one of his emollients to cure lepers and stop seizures. In his excellent book, “Marijuana the First 12,000 Years”, David Ables spends a page or two speculating on the origin of the word marijuana or marihuana.

Ables suggests that the origin of the word marijuana could be Spanish, Moroccan, Chinese or Portuguese. My guess is it was based on the Portuguese word maryerona or maran griago which connotes intoxication. In the eighteenth century Swedish botanist Linnaeus developed the standardized plant nomenclature still used today. He gave cannabis its proper name, Cannabis sativa L.

Soon after being introduced in New Orleans around 1890, cannabis (aka muggles, reefer, Mary Jane) was being used by the jazz musicians who provided the background music for the houses of ill repute in the red-light district, called Storeyville, named after City Councilman Story who had designated that area of town for these whore houses with jazz accompaniment.

But the real confusion between cannabis, hemp and marijuana came with the Mexican Revolution. It started in 1910 and sent millions of Mexicans fleeing to the U.S. and bringing with them not only cannabis but the word marijuana. Hearst owned a string of newspapers. He had previously shown his anti-Hispanic colors by using his newspapers to gin up hysteria and support for starting the Spanish-American War. It propelled America’s entry into colonialism.

It was Hearst who popularized the word “marijuana” in his effort to play to the anti-immigrant sentiments of the American public in his to attempt to marginalize these Mexican immigrants seeking refuge from the ravages of war.

For the next three decades we had the odd situation of over half the states in the U.S. declaring marijuana as illegal, cannabis being available in over 25 over the counter medicines and, in the 1920s, doctors writing three million cannabis containing prescriptions a year.

In the 1930s the petrochemical industry entered the name game. They were concerned about competition from hemp. Why is that, you ask? In the 1920s and 30s it was not clear that fossil fuel would be the fuel of choice for automobiles and the internal combustion engine. Henry Ford always thought that the internal combustion engine would run on plant-based ethanol. His choice was hemp ethanol. In the late 1930s, Ford developed a prototype car that not only ran on hemp ethanol, but whose upholstery was made of hemp and whose acrylic body was embedded with hemp.

There is strong circumstantial evidence that Lamont DuPont of Dupont was the point man here. Dupont had many products that would be threatened by competition from more affordable hemp. Hemp was now competitive due to a harvesting machine (decorticator) patented in 1916 that cut in half the labor needed to harvest and prepare hemp for industrial use. By 1933 the original patent ran out and large agribusinesses could see profits in the near future from growing hemp. In fact, in 1938, only months after the Marihuana Tax Act (MTA) was passed, Popular Mechanics ran an article entitled “Cannabis the New Billion Dollar Crop.” As Jack Herer pointed out in The Emperor Wears No Clothes, hemp is very versatile. It has been used in building materials, fiber, as a medicine, a food, as well as a social lubricant. Herer said that cannabis had 25,000 industrial and medical uses.

The inner core of hemp, the hemp hurd, was basically a waste product if you were growing hemp for fiber, food or oil from the seed. The hurd is cellulose. Dupont, a munitions maker, used cellulose not only for munitions, but to make the synthetics cellophane and nylon. Dupont also made sulfites used to make paper from both wood pulp and hemp. However, wood pulp required four times as much sulfites to make paper as hemp. Dupont also made the gasoline additive tetraethyl lead which would fall by the wayside if cars were powered by hemp ethanol. Henry Ford always thought cars would run on ethanol, most likely hemp ethanol. In the late 30s Ford had a prototype car with hemp upholstery, hemp biofuel and acrylic skin made from hemp that was 15 times stronger than steel. Finally, Dupont was the largest shareholder in Ford’s major competitor, General Motors. While there is no smoking gun, there is ample circumstantial evidence that Dupont was the driving force behind the MTA.

The clincher in this pile of circumstantial evidence is that the MTA was introduced in the house by Robert Doughton (D- North Carolina). He was a long-time water carrier for Dupont and had previously introduced legislation at Dupont’s behest.

Harry Anslinger, the first director of the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (now the Drug Enforcement Administration) was arguably the greatest bureaucrat of all times. He created a problem where none existed by demonizing cannabis. Well, he couldn’t demonize cannabis because way too many people knew what cannabis was, but he could demonize marijuana.

It’s hard to comprehend today but in the 1930s few Anglos used cannabis recreationally and cannabis was, well, cannabis. While jazz musicians and some African Americans used cannabis recreationally, they usually referred to cannabis as “muggles” or “Mary Jane”. In his autobiography, the great trumpet player Louis Armstrong wrote that his daily use of “muggles” was the only thing that allowed him to deal with the rampant racism in America. And of course, the Mexican American population constituted a much lower percentage of the U.S. population than it does today. The American populous knew what hemp was. They knew what cannabis was, but marijuana was a word that was foreign to the ears of the vast majority of Americans of the 1930s.

In their vigorous 1937 testimony AGAINST the MTA, the American Medical Association said that they almost didn’t show up to testify because they had no idea that the MTA was about cannabis. They testified that should the MTA pass over the AMA’s opposition, it should be renamed the Cannabis Tax Act so the American public knew what the law was talking about. Clearly the medical establishment’s testimony was ignored.

In the mid-1990s Michael Krawitz, a drug policy reform activist, communicated with the pioneering ethnobotanist Dr. Richard Schultes, a Harvard Professor. In a letter to Krawitz, Shultes explained that hemp and marijuana were the same plant. He went on to say that the less than 0.3% THC as a red line between hemp and marijuana was an arbitrary bureaucratic fiction. It had no basis in botany. Hemp and marijuana are one and the same. They are cannabis.

Comments 2

Great article. I recently wrote a white paper on patent activity in cannabinoids where I touched on a tiny bit of the history.

We need simple, easy-to-follow COMPLETE plans of how to use Cannabis medicinally by people who have done PROVEN or at the very least, properly researched, complete with source links. Maybe one for prostate, one for melanoma, etc, etc. Even if it is just the essentials – CBD:THC ratios and dosage suggestions.

That’s the biggest practical hurdle (apart from the street prices).

We all hear, “Take weed mate.” But what does that actually mean?