When Landon Riddle was just 2-years-old he was diagnosed with leukemia so aggressive, the doctors gave him a 10% chance of living through the first 24-48 hours.

Landon was living with his grandmother, Wendy, in St. George, Utah when she noticed the glands on the side of his neck were swollen. Doctors assumed his body was fighting an infection and that they should just give him rest, fluids and monitor his condition.

Wendy became increasingly concerned when Landon didn’t get better and they had the doctor prick his finger again to test for infection, which came back negative. Landon was playing, eating, sleeping, and drinking and so everyone assumed that he was just fine after two blood tests. A couple of days later while spending the night with some friends, they noticed that Landon’s groin was now swollen and rushed him to the hospital and then reached Wendy.

Landon’s blood work (complete CBC) came back positive for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-cell ALL). T-cell ALL is an aggressive form of cancer that can be fatal within months if left untreated. Landon was airlifted four hours north to Children’s Primary Hospital in Salt Lake City. When they arrived there was a team of 20 doctors, nurses, and technicians waiting to treat him.

“They weren’t giving him a good chance of survival at that point,” says Sierra Riddle, Landon’s mother.

Sierra wasn’t there at the time of Landon’s diagnosis because she was also fighting for her life. Sierra has suffered from foot injuries and severe endometriosis since she was young. Her diagnosis of endometriosis resulted in a hysterectomy after Landon was born. She lived in an immense amount of pain.

“In Utah, the only answer was to put me on narcotics, it led me down a dangerous path,” Sierra says. “Nobody wants to talk about the rate of the over-prescribing of narcotics.”

After a complicated foot surgery to both of her feet, doctors prescribed Sierra three to five different opiate drugs, including OxyContin, to manage the pain. She became physically dependent on the drugs to prevent the symptoms of withdrawal. After she could no longer afford the drugs she needed to prevent getting sick, she turned to heroin to dull the pain.

“It ruined my life,” she says.

According to the Utah Department of Health, an average of 21 Utahns die of a prescription overdose every month and opioid painkillers are now a leading cause of death. In 2012, Utah doctors wrote prescriptions at a rate of 85.8 per 100 people in the state. Oxycontin, and other legal opiate painkillers, are highly addictive and pharmacologically similar to opium-derived drugs such as heroin. Heroin addiction has now become an epidemic in Utah.

Shortly before Landon’s diagnosis, Sierra checked herself into rehab in Georgia. When she learned of Landon’s diagnosis, she checked out of rehab with just 45 days sober and flew to Salt Lake City to be with her son and family.

“I felt so much guilt, I felt like a terrible mom,” she says. “When I walked in and saw him and he was so swollen it didn’t even look like him. I didn’t even recognize him.”

Landon’s treatment was traumatic for the whole family, particularly Landon. He had to be strapped down, including his head, and forcefully given oral medications and other procedures that were invasive and incomprehensible at his age.

“To him, that is torture, he had no understanding of what was happening,” Wendy says.

Wendy recalls a particularly traumatic incident when doctors came to access his chest port. He was sitting on her lap and when they were getting ready to start, he jumped up and ran to a corner, where he cowered and put his hands over his head and cried.

“He looked at me and said, ‘Grammy, please don’t hurt me anymore,’ because in his mind, because I held him and had to hold his arms and legs down to do all this, I was the one who was letting them hurt him,” Wendy says. “I don’t know that he is ever gonna forget that… I don’t know that I am ever gonna get past that.”

Landon’s body became covered with bruises from struggling under the hands of his mother, grandmother and doctors as they held him down to force-feed him pills and undergo invasive procedures.

“Landon decided at that point that there was no defeat and no surrender,” Sierra says.

Due to the high volumes of chemotherapy and radiation Landon was undergoing, his doctors advised them to go home for two weeks so his body could recover from the treatments before they gave him more. He rarely slept, he was on three to five medications for the pain and was constantly vomiting. He stopped eating.

Sierra and Wendy started getting desperate; it became clear Landon was going to die. They turned to friends and family on Facebook pleading for suggestions, miracle treatments they hadn’t heard of—anything to save Landon.

A close friend sent Wendy studies about medical cannabis. Wendy, having watched Sierra and other family members suffer from addiction, was vehemently anti-drug and livid that a friend suggest she give marijuana to her 2-year-old grandson.

“My views on cannabis, to say the least, were evil, evil, evil,” Wendy says. “I was hot on the keyboard writing her back. I was hurt, I was angry. I felt like my friend had just slapped me.”

Her friend replied calmly back, urging her to at least read what she sent once she had calmed down. Two weeks later Wendy opened the email and started reading. She said she had been expecting “hippie pot-smoking crap” but instead found well-researched medical studies and articles about how cannabis works in the body and how it can treat cancer. She dove further into research and called three separate doctors to learn what she could about maybe giving Landon cannabis.

Wendy says it was hard to find answers because there weren’t many people treating kids with cannabis for cancer, and no one who she could find who had treated a child as young as Landon. What they did learn was that cannabis couldn’t kill him, and with nothing left to lose—Landon was dying—they decided it was worth a shot.

During the two-week chemo break, they drove Landon to Colorado to try cannabis. At the time he was attached an IV-bag 24 hours a day to receive fluids and nutrition, the drive was hard. He hadn’t eaten in almost six weeks. He had lost nearly half of his body weight and was unable to walk.

“I will never forget. We loaded Landon in the car, we brought him to Colorado and the very first dose—within an hour and a half—I was holding him and his whole body just relaxed,” says Wendy. “I just held him and cried, I’ll never forget that.”

Landon continued to sleep 18 hours or more for the first five days of his treatment with cannabis oil. When he woke up on the fifth day, he asked for food. He asked to be held, which was very painful for him up to this point.

“He started smiling again, that was something that was huge for us. He hadn’t smiled or laughed in a very long time,” says Sierra.

The results solidified their decision. They continued to treat him with cannabis and he progressively got better, eventually weaning off all of his prescription painkillers. He continued the chemotherapy alongside his cannabis treatment for another five months but needed less hospitalization, drugs, narcotics, and blood and platelet transfusions.

“He was getting better, he kept getting better. It got down to the point where, knowing his medicine was illegal in Utah, and knowing that it was saving his life, we had to decide to move, to leave Utah behind,” Sierra says.

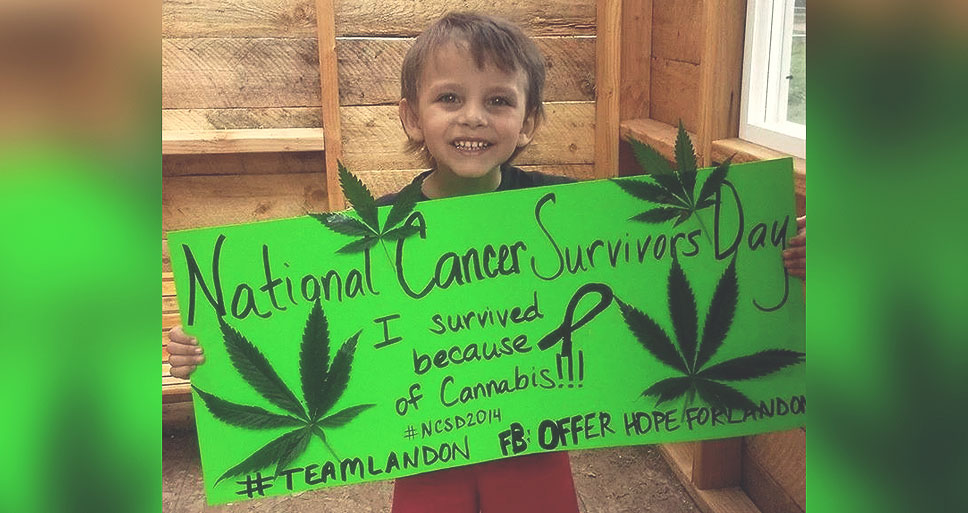

Today, Landon is in remission. He is a healthy, energetic little boy who just turned 5-years-old in February. Sierra has been clean for three years. Doctors offered her narcotics and anti-anxiety meds to help her stay calm for Landon’s treatments, but she refused.

When Wendy saw how cannabis saved Landon, she did more research and learned how cannabis could also help treat opiate addiction—which is usually treated with more opiate drugs, like Suboxone, making it difficult to ever recover fully from the addiction and physical dependency. Recent studies have shown that cannabis can successfully treat addiction to opiates. Sierra used medical cannabis to get and stay completely clean.

“It was night and day, it saved her life. I don’t know how much longer she could have held on until she slipped back into addiction. When she started medical cannabis everything in her life got better. The plant saved both of their lives,” says Wendy.

“I have taken control of my healthcare, I have taken control of my son’s healthcare,” Sierra says. “We are thankful to be here in Colorado but we want to come home. We want to go home to Utah.”

Landon and Sierra cannot visit Wendy or the rest of their family in Utah unless they leave Landon’s life-saving medicine behind.

“It is ridiculous that a child cannot go and visit his grandmother because the medicine he takes is illegal,” Wendy says. “The way [that] made me feel for a long time was incredibly angry, but as I gained more knowledge and more awareness I began to realize that people are not trying to block this plant medicine out of spite. People are scared, they have been fed so much garbage and false information—lies—that they believe it, just like I did. They are afraid of what they don’t know. It hurts, but I also understand the key is helping to educate our legislators so they begin to understand this.”

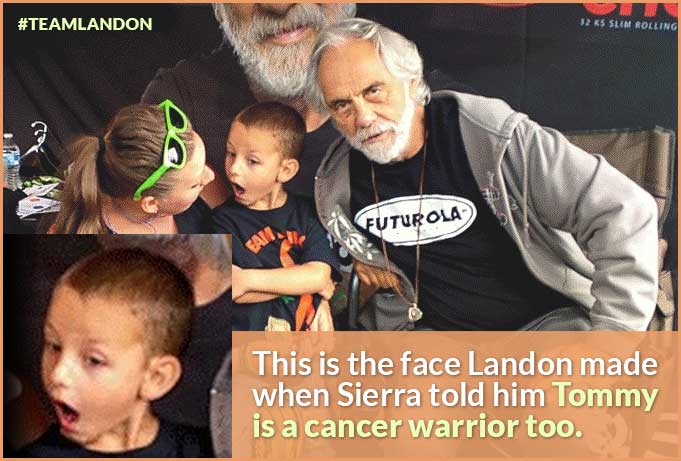

Update: In August of 2015 Landon had the opportunity to meet fellow cannabis patient and cancer warrior Tommy Chong.

This is the face Landon made when Sierra told him Tommy is a cancer warrior too. Seattle Hempfest day two done! We are BEAT!!! See you tomorrow! @OfferHopeForLandon